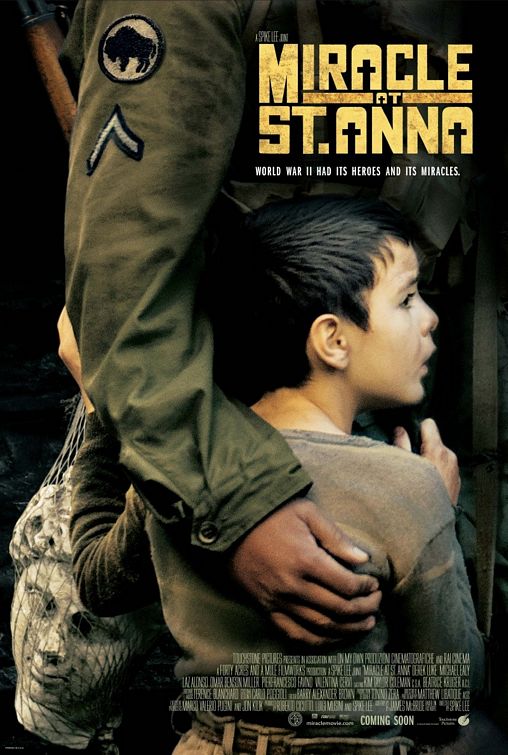

MIRACLE AT ST. ANNA

2008

Written by James McBride, based on his novel

Directed by Spike Lee

It's interesting to see a filmmaker with as distinctive a vision as Spike Lee taking on a war movie. I can't really think of another point of comparison here; maybe Steven Spielberg, but his vision has always been more in his themes than in his execution. Lee made the jump to clever mainstream fare with Inside Man two years ago, and Miracle at St. Anna should've been the next step, a big war movie with an epic running time of close to three hours. Instead, it's a mess. A well-intentioned mess, but a mess nonetheless.

The film opens in the 1980's as Hector Negron (Laz Alonso), a former black Army Corporal, watches John Wayne's Sands of Iwo Jima on TV and angrily mutters, "We fought in that war too, pilgrim!" (Did you know that Spike Lee hates John Wayne? Me neither!!!) Negron now makes a living as a postal worker, a run-of-the-mill job until one day he inexplicably pulls out a German Luger and shoots a customer. An eager young reporter (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) takes interest in the story when no one else does, and convinces a detective (John Turturro, in another worthless supporting part) to allow him to visit Negron in prison. There's also some business in Italy where some Italian-American playboy (John Leguizamo, taking another hit after the unfortunate one-two punch of The Happening and Righteous Kill) has steamy sex before dropping his American newspaper out the window, where it lands in the hands of an Italian man who sees the headline about Negron and starts running around shouting something about "the sleeping man." This is the most unnecessary sequence ever.

Negron begins telling his story to the reporter, and this sloppy framing device is left behind until its hurried, obligatory denouement at film's end. We now enter the Nazi-occupied Italy of 1944, where we eventually learn all about "the sleeping man" and why Negron shot his customer, though it's hard to see why we should care. We follow the all-black 92nd Infantry Division as they get trapped in a Tuscan village, where they stay with an Italian family while attempting to contact headquarters. There's also a little boy named Angelo (Matteo Sciabordi) who befriends the overly simplistic and even stereotypical Private First Class Sam Train (Omar Benson Miller), a giant of a man described at one point as being "the biggest Negro you've ever seen."

What's shocking is that in setting up all of these storylines, Lee treats it as a comedy. I'm not just talking about the fleeting bits of morbid humor in Apocalypse Now or Saving Private Ryan, or even the bleak satire of something like MASH, but straight-up, belly-laughing comedy. There's always been an uneasy relationship between drama and comedy in Lee's films, and here it is at its most evident since the abysmal She Hate Me. The first hour of the movie is horrible; it's like Lee's camera is a piano he forgot to tune, bashing away and getting every note wrong. Perhaps the most painful moments come between Train and Angelo, the simple Negro tenderly communicating with the precocious kid in scenes which are both uncomfortable and condescending.

The other soldiers are a little less obvious, and when their personalities begin to emerge in the second half, the film abandons most every pretense of comedy to deliver some serious drama. It's an awkward shift, but one which is more than welcome. Staff Sergeant Aubrey Stamps (Derek Luke) falls in love with Renata (Valentina Cervi), the only person in the Italian family who can speak English, while the slick Sergeant Bishop Cummings (Michael Ealy) is determined to get into her pants. This storyline, and the dynamic between Stamps and Cummings, is tedious like the rest, but provides the movie with one of its finer dramatic moments, a quiet conversation outside a dance hall about the black race and where it belongs. It's one of Lee's more familiar elements, but in this case, that's a good thing; in a film where he so often seems in over his head, it doesn't come across so much as a retread as it does Lee finding the right context in which to address his intent.

That intent, as with many of Lee's movies, is thuddingly obvious. He isn't usually a subtle or restrained filmmaker (25th Hour was an exception for the most part, and Malcolm X was where his approach really worked), but at least in movies like Inside Man or his beloved Do the Right Thing, he approached racial politics with a sense of bravery and wit. Miracle at St. Anna, unfortunately, boasts a stack of tired ideas and half-baked executions. A scene in which the soldiers are refused ice cream at a redneck diner, while white soldiers and even captured Germans partake of the dessert, could've been one of the film's most powerful and searing moments, but instead is a none-too-shocking reprise of the kinds of over-the-top racial injustice we see so often in movies like these. To be fair, this is the first major production about the all-black infantry, and things like the diner scene really did happen, but it still feels phoney.

Make no doubt about it, Miracle at St. Anna is just as filled with righteous anger and fiery passion as Lee's other movies. But he is swallowed by that passion, not knowing when to stop or reign things in. The idiotic farce in the first half demeans the tragedy of the events, and the self-seriousness of the second half is indulgent and long-winded. There is one sterling sequence, in which we witness what happened at the titular St. Anna, but the film is short on miracles. The movie doesn't fail because I'm white and haven't lived the black experience, a criticism I've already seen aimed at other reviewers. The reason the movie fails is that just because Spike Lee had something worth saying, doesn't mean that he said it well.

- Arlo J. Wiley

September 29, 2008

Review Archive

Back Home